Eatin’ Crow

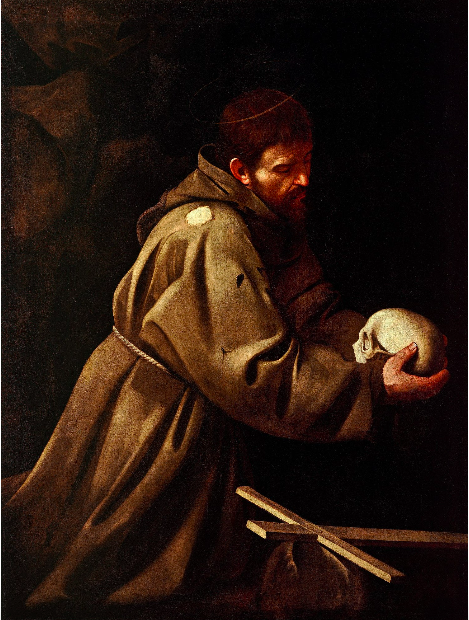

Saint Francis in Prayer by Caravaggio

At roughly 6:30 PM on the evening of July 28, 2013, I stood before my home church, my short sixteen-year-old frame barely visible behind the pulpit, and delivered what would become my first sermon. My primary text was Hebrews 11:17, and just as “Abraham, when put to the test, offered up Isaac,” I trembled before the congregation attempting to prove that I, too, was willing to pass God’s test of walking away from what I cherished most. With no time to look back, I was in urgent pursuit of the vocational call that shook the very foundations and sensibilities of the life I had been building up to that moment. As my sermon concluded, I made my public announcement before friends, family, and God that I was enlisting myself into the service of God’s Kingdom by preaching and proclaiming the Gospel of Jesus Christ. In my mind, my life was no longer my own, and to the degree I was able, I was offering my gifts and my possibilities up to God as a piece of clay to be molded and shaped by the One who knew me better than I knew myself. Terrified and determined, I jumped into the deep end of serving God’s people, utterly oblivious to the fact that my stature, age, lack of theological training, and experience had perhaps already disqualified me from any sort of serious consideration of being a “Reverend.”

This weekend I am celebrating ten years of ministry and still reaping, both the blessings and the curses, from the declaration that I shared a decade ago. The great irony of that night is that the certainty with which I began my rigid and planned-out ministry changed the course of my life just enough at sixteen to arrive at some unexpected, unplanned, and uncharted shores at twenty-six. Perhaps like many of you, there is a part of me that is enticed by the temptation to quickly dismiss the premature decision of an ambitious and naïve kid. However, I can hear that familiar voice of silent invitation, the one I heard and initially resisted as a Sophomore in high school, still calling me deeper into the mighty current of God’s redeeming work.

Although if I’m honest, I no longer pretend to know what God is doing with my life. I’ve learned that God loves to interrupt our hubris and seriousness with divine comedy, reminding us that we were never as in control as we thought we were. Yet, it has been in these moments that I’ve been strengthened by a hope that trusts, against all odds, that God doesn’t need perfection or preparedness to begin a good work in our lives nor to complete that work (Phil. 1:6). Time and time again, God has shown me that God isn’t scared to get in the middle of our mess and work within the mistakes we have and will make. This isn’t to justify or romanticize our mistakes, especially those that cause harm to our neighbors, but I do think it says that God simply asks us for a raw and gritty faith that trusts deeply in the incomprehensible absurdity and profound gravity of God’s Kingdom, come what may. 1 Corinthians 1:27 reads, “But God chose what is foolish in the world to shame the wise; God chose what is weak in the world to shame the strong.” I suppose that criteria still applies for those of us senseless enough to accept and pursue the plans and desires God has for our lives.

I don’t ascribe as much value to my ten years of ministry as I do the wisdom of older saints who have experienced a lot more life than me, but I still think God has taught me a great deal about “callings” and “vocations” after I, rather blindly, stumbled into my own as a teenager. I’ve come to believe that much of vocation is about learning to ’eat crow.’ For those unfamiliar with the phrase, my family would always say that you had to “eat crow” once you realized that you were, in fact, gravely mistaken after asserting some false claim with complete confidence. We probably could have just said it was a “pill too big to swallow,” but nothing quite paints the picture of one’s foolish ignorance like the image of having to choke down a gawking crow.

In a lot of ways, vocation, what I understand as the commitment to live in accordance to God’s Truth revealed in Jesus Christ and the consequent freedom we inherit as a result, is a lot more like eating bitter crow than we’d like to admit. In my experience, the Truth has hardly ever been the mirror that has made me feel good about myself after exposing all the ways I had deceived myself and others. Truth, and I mean the real, ugly, and naked Truth, exists as the very ground of our being and stands as the eternal reminder that all of creation forever rests in the loving gaze of God. Unfortunately, much of what we call truth, freedom, and vocation in our culture is more informed by fear and greed than it is by grace and love, distorting the ways we see our lives, our ministries, and the paths God has invited us to walk.

To be clear, I don’t think preachers, missionaries, and theologians have a monopoly on vocation and being “called to ministry.” Sure, there are those of us who perhaps feel that our gifts are much better suited for professional ministry than some other working profession, but I think any notion that we have somehow been “chosen,” as if in some VIP club, is misleading at best and harmful at worst. As a good baptist, I deeply believe in the “priesthood of all believers” (inferred from 1 Peter 2:9). I’ve always understood this verse to be a proclamation that each of us are endowed with a vocational call to love and serve God by living into the fullness of our gifts, talents, and passions but also in ways that makes real the healing and transformative power of God’s love to the world around us.

However, let us not deceive ourselves into thinking this is some sweet and sentimental undertaking that we can pick up and put down as we like. No, no, vocation is a death of sorts. It is the death of our right to ever claim we have possessed absolute truth. It is the death of our tendencies to take the world as it is for granted, consenting to the normalcy of a world beaten to a pulp by war, greed, and hate. It is the death of perpetual comfortability and complacency. The Christian vocation is death because, once we realize the glory of God is the gory God revealed in Christ, we cannot go on under the illusion that life is about anything other than love. The soul’s detachment from our illusions certainly feels a lot like being buried six feet under the cold and dark earth, at least that has been the case in my experience. In the words of Carl Jung, “No tree, it is said, can grow to heaven unless its roots reach down to hell.”

Following the Way of Jesus from our particular vantage point, which is our vocational call, is about accustoming ourselves to the hellish pain of accepting our weaknesses, our limits, and our foolishness as the very cornerstones of our strengths, our possibilities, and our comprehension of Truth. I’d argue most of us already know, to varying degrees based on our social location in a society seemingly allergic to conflict, that life is inherently fragile and that the spiritual path is learning to befriend our fragility. However, we tend to deliberately ignore or outright reject the crow-tasting, bitter truth on the grounds that real faith in a crucified God is far too costly. It is not only costly to our own intolerance towards discomfort but also to our aggressive defenses against admitting that we were wrong, perhaps, because our parents, grandparents, friends, evangelists, coaches, teachers, and beloved pastors were wrong as well. You see, when we boil down our society’s lack of faith in anything other than a “business as usual” worship of war and profit maximization, we begin to see that most of us upholding this political and economic regime do so not out of stupidity or maliciousness. Rather, it is because we are scared of being lonely, scared of being rejected by the very people who taught us what love was in the first place. As a consequence, far too many of our churches have mistaken self-righteous intoxication for discipleship after discovering the road to Golgotha isn’t traveled by many caravans.

It’s hard to imagine sanctification without repentance and even harder to imagine vocation without relentless pursuit of the One we think we know but don’t. Ministry, in whatever form that takes for us, is less about expertise and perfection than it is about humility and desire, a desire to walk with God and not be God. Our callings are not badges of unquestionable authority and power but rather crimson marks that we have tasted and seen that the Way, the Truth, and the Life is good and just and beautiful. Vocation is the adventure of tethering ourselves to the scarred feet of Jesus along the unmarked path of exploring the mysterious and wondrous life of the Triune God. It is in this divine life, in the deepest unforeseen depths of God’s love, that we are safe enough to admit just how much we don’t know about God, life, and ourselves.

All that to say: a decade of ministry has shown me that I don’t know a thing. Ten years ago I was absolutely certain I knew who God was, why Abraham was going to sacrifice Isaac, and what my ministry was supposed to look like. Today, all I know is that I’ve had to eat a lot of crow and had to live with the regret of how much hurt I’ve caused my neighbors, my congregants, my friends, and my family. My mistakes haven’t stopped my ministry, although I’m sure there are some out there who wish they would have. On the contrary, they have expanded it, showing me that God can be found just as much in the dirtied hands I hold in the streets as in the pedicured ones that applauded me under the steeple.

If I could preach on the ten year anniversary of my first sermon, I think I’d still preach the same text. I’d preach about a conflicted father and a scared son. I’d still make the connection that the spiritual path of vocation is admitting, in some ways, that our lives are no longer our own. However, I wouldn’t begin my altar call asking for folks to come and be willing to sacrifice themselves to a scheming God content with child sacrifice. I think, instead, I’d question whether or not Abraham was too attached to an idea of God that looked more like himself and the people around him than a gracious Creator. I’d wonder how Abraham’s theology justified the murder of his own flesh and blood and what it meant that Abraham, even in his reluctance, was still willing to give his son over to a God that needed appeasing lest his wrathful anger bubble over into further catastrophe. I think I’d invite folks to come and meet the God we could have never expected, the One who was revealed at the last moment as the God more interested in communion than sacrifice. Then as I closed, I’d probably invite my hearers to imagine their lives if they let go of the “God” they think they have to believe in and instead, open their hearts and minds to the God revealed in the crucified Christ. I’d ask if they could fathom rearranging their lives around the One who clothed Himself in fragility, the One who loved His own enemies, the One who gloried Himself in thorns and blood, and the One who defeated death with a grave. And before inviting everyone to come pray or make some life-changing decision, I imagine I might warn them this time and say:

The hardest and most brutal part of ministry and following Jesus is never quite getting comfortable with the fact that he, that God, is hardly ever who we want him to be.